There’s no-one to root for in this nihilistic spectacle about the horrors of war, as the characters “march towards annihilation”.

“Perhaps all men are corrupt,” says Ser Cristen Cole in the House of the Dragon finale. “And true honour is a mist that melts in the morning.” It is, as his fellow concerned knight offered, “a bleak philosophy” but it is one that felt fitting for a season of television primarily concerned with exhibiting the human cost of war.

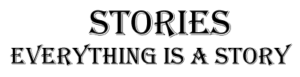

While the marketing campaign for the second series of the Game of Thrones prequel urged fans to declare for either Team Green or Team Black, the show’s warring factions, the series itself seemed determined to make the case for neither. Its final episode concluded a season of sacrifice: of hopeful bastard dragonriders, of firstborn sons and of principles. The bar for ethical behaviour is low in Westeros but still few people clear it, so locked are they in mutual destruction.

Instead it was the words of doomed Rhaenys that came to define this second season: “Soon they will not even remember what it was that began the war in the first place.” Her correct prediction of a self-perpetuating cycle of destruction was both a nod to the source text Fire and Blood (written as a series of retrospective scholarly histories that do not always concur) and a sign that despite ostensibly mirroring its predecessor in being about who should (and who actually will) sit on the Iron Throne, this series is actually about a long, slow and brutal descent into the nihilism of war for war’s sake. Early on, we saw how the Rivermen used the Targaryen infighting simply as a convenient excuse to escalate an ancient feud, and by the finale, we had Cole cooly accepting: “We march now toward our annihilation”.

Part of this dreary outlook comes from the show being a prequel and a pre-existing book. Whether or not viewers have read Fire and Blood, the events of Game of Thrones have told us that the Targaryen house all but destroyed itself – and its dragons – in this war. We know already that there is no happy ending, but it has increasingly seemed that the characters themselves agree. With the devastating realities of dragon warfare unveiled, it has become a conflict fought by either those who relish destruction or those who are resigned to it, with Rhaenyra falling somewhere between the two.

In Game of Thrones, there were characters only really out for themselves, and characters who claimed to be fighting for a greater good – but the overarching malevolent threat of the White Walkers provided an indisputable enemy and a call to arms that could not be ignored. In House of the Dragon, we have a war predicated on a terrible misunderstanding, fuelled first by a thirst for power and then by retaliation and vengeance, and fought using weapons of total devastation.