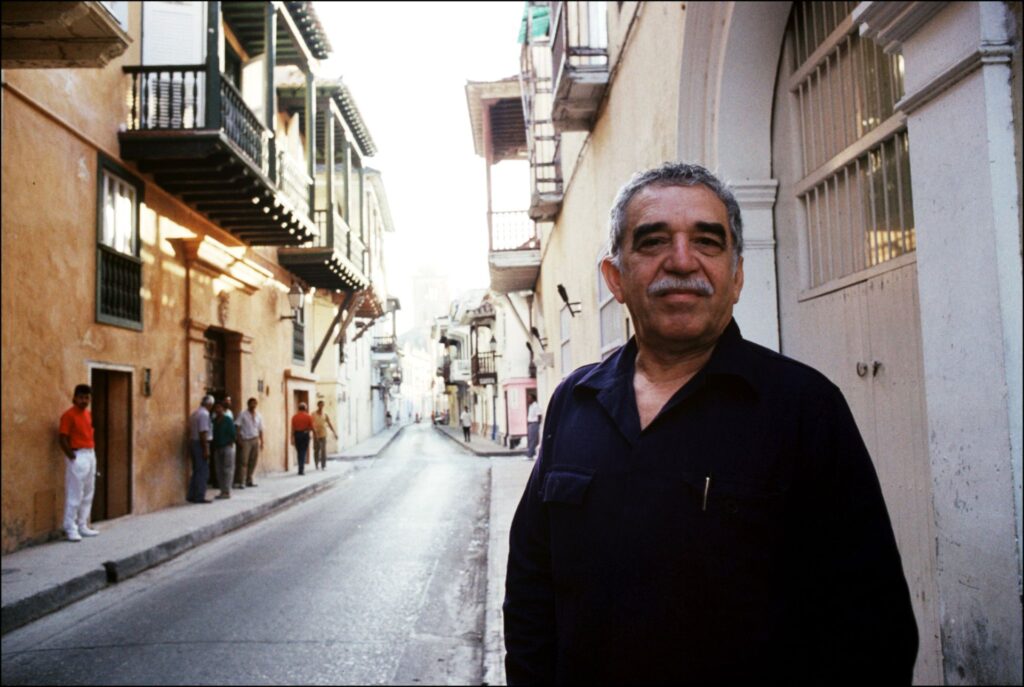

The Netflix adaptation of ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ provides an opportunity to appreciate the novel’s artistry and the legacy of its author, Gabriel Garcia Marquez

“I have seen many great films based on very bad novels, but I have never seen a great film based on a great novel,” wrote the Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez in 1982, the same year he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature.

He was no longer the little-known writer he had been while writing “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” This book would go on to sell over 50 million copies in 32 languages and is frequently ranked among the most influential novels of the 20th century, solidifying Garcia Marquez’s reputation as the master of “magical realism,” a literary style that remains immensely influential worldwide.

In 1966, Garcia Marquez completed the novel while living in Mexico, during a time of financial hardship. At one point, he owed nine months’ rent and couldn’t even afford to mail the manuscript to his editor in Argentina. Sixteen years later, by 1982, he had become a literary supernova, regarded by many as the greatest living novelist writing in Spanish. As his fame grew, so did the opportunities that were once scarce, including million-dollar proposals for film and television adaptations of his works. But despite these offers, Garcia Marquez adamantly refused to sell the rights for “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” “I want to communicate with my readers directly,” he explained, “through the words I write for them.”

Garcia Marquez expressed his objection to having his works adapted for the screen in multiple newspaper articles and interviews. Yet in 2019, five years after his death, Netflix announced that it had acquired the rights to turn “One Hundred Years of Solitude” into a limited series. Unsurprisingly, the news sparked controversy. Many criticized the author’s children — the heirs to their father’s literary estate — for having “betrayed” Garcia Marquez’s lifelong wishes by allowing Netflix to purchase the rights to adapt the novel.

At the time, too, the Latin American literary community was divided over the news. Some well-known figures, such as the Argentine writer Mariana Enriquez, shortlisted for the International Booker Prize for her brilliant novel “Our Share of Night,” expressed their reservations, suggesting that it was unethical to contravene the express will of the dead. Others, such as Alvaro Santana-Acuna, professor of sociology at Whitman College, were less harsh in their judgments, arguing that the series would be an excellent opportunity to both pay homage to a literary giant and introduce the novel to new audiences who might otherwise never engage with it.

With the upcoming release of the series on Dec. 11, the controversy has resurfaced, along with renewed interest in the novel — almost 300,000 copies were sold just in Japan over the summer. Consisting of two seasons of eight episodes each, Netflix describes the adaptation as “one of the most ambitious audiovisual projects in the history of Latin America.” Although the exact figures are unknown, its substantial budget and production scale indicate Netflix’s high expectations for its success.

The release of Netflix’s adaptation of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” offers a valuable opportunity to explore several timely, controversial questions. Much has changed since Garcia Marquez’s lifetime, especially in technology, the video streaming industry and storytelling techniques. Would he hold the same views today? Moreover, the debate surrounding the Netflix adaptation provides a lens to fully appreciate the novel’s artistry, Garcia Marquez’s insights into the art of fiction and the troubled path of his legacy over the decade since his death.

Netflix’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” is not the first screen adaptation of Garcia Marquez’s works. At least a dozen have been made by both Latin American and foreign filmmakers. Perhaps the most successful example is Arturo Ripstein’s 1999 film “No One Writes to the Colonel,” which competed for the Palme d’Or at Cannes. By contrast, Mike Newell’s 2007 adaptation of “Love in the Time of Cholera” was a notable critical and commercial failure. The Guardian’s film critic, Peter Bradshaw, scathingly described it as a “horrifically boring festival of middlebrow good taste.”

Garcia Marquez himself was a prolific screenwriter, whose credits include numerous short films and as many as 10 feature films. He studied film in Rome and, in the 1980s, he co-founded the International Film and TV School in San Antonio de los Banos, Cuba, a leading institution for filmmakers and screenwriters in Latin America that has survived to this day.

“The only thing I have studied systematically in school is cinema,” he once said. “I never studied literature, I completely ignore the rules of Spanish grammar; I write by ear.” These remarks, as well as his lifelong involvement with cinema, indicate that Garcia Marquez was not a “literary supremacist,” so to speak. In other words, he didn’t think that the written word was inherently superior to cinema as a storytelling medium. Yet, on several occasions, he stated that he never wanted “One Hundred Years of Solitude” to be turned into a film or series. What inspired this refusal?

The novel tells the story of seven generations of the Buendia family. Though its members’ lives take very different paths — one becomes a colonel, another a sailor and a hunter, another an aging matriarch who sells candies to sustain the household, one a cockfighter, another rises into the sky forever, and so on — they seem fated to repeat the same cycles. They’re either existentially paralyzed by introspective solitude or driven into ruin and isolation by chimerical fantasies. Interspersed with the tale of this family is the story of the fictional town of Macondo, which evolves from a small village into a prosperous, jovial yet troubled community, finally turning into a decrepit shell that displays little of its former glory: abandoned, decaying and steeped in nostalgia.

One reason the novel was, and remains, so popular is that it is perceived to have captured something profound about the history and experience of Latin America. Emphasizing its oral, rural, magical, family-centered and convoluted perspective on reality, many readings of the novel claim that it offers a vivid contrast to the European worldview — rational, restrained, individualistic. Regardless of the accuracy of this comparison, the novel undeniably redefined what Latin America meant in a global context, to the point that it is often seen as its most comprehensive portrayal. Gerald Martin, the author’s biographer, described it as “the grand, all-embracing, far-reachingly metaphorical narrative of the continent.”

Garcia Marquez was concerned that an adaptation would strip the novel of its connection to Latin America, erasing from the story the qualities that made it an embodiment of the spirit of the region. In a 1987 interview, he suggested that it would be disastrous to have Hollywood actors performing as the main characters, thereby imposing American or European faces on people from the Latin American Caribbean. He disapprovingly remarked that an adaptation of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” would be “so costly a production that it would have to be with big stars, De Niro as Colonel Aureliano Buendia or Sophia Loren as Ursula.”

Garcia Marquez’s anxieties highlight how the landscape of the film and television industry has evolved in the past three decades, opening room for possibilities that were once unthinkable. If there’s one thing that seems to be needed for a complete adaptation of “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” it’s a sizable budget to capture its intricate, meandering plot, which features a multitude of characters and settings that change dramatically across time. Equally important is the use of special effects, essential for portraying the fantastical elements of the story — which make it the paradigmatic example of magical realism. In the 1980s and ‘90s, as Garcia Marquez said, such a production would have involved casting major Hollywood stars to guarantee its financial success. Today, with the consolidation of a global market and the rise of streaming platforms, star power is no longer required to make a hit among audiences. Think of the massive global success of the South Korean series “Squid Game” or the Spanish drama “Money Heist.” Both resonated widely with international viewers despite not casting international figures and not being shot in English.

If Garcia Marquez was worried that an adaptation would not stay close to the source material, Netflix seems determined to assuage this concern. The adaptation’s original language is Spanish, and it was entirely filmed in Colombia. Hoping to capture every detail as faithfully as possible, Netflix built a full-scale replica of Macondo, spanning nearly 130 acres and involving around 20,000 extras.

To further emphasize Latin American involvement, all episodes are directed by two established filmmakers from the region: Laura Mora, winner of the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian Film Festival for “Killing Jesus,” and Alex Garcia Lopez, whose directing credits include popular American series such as “Fear the Walking Dead” and “Daredevil.” Additionally, two of Garcia Marquez’s sons serve as executive producers, one of whom is Rodrigo Garcia, a film director in his own right.

The series is not a whitewashed, decontextualized rendition that lacks authenticity and local flavor. If anything, it leans too heavily in the opposite direction, at times overindulging in its pursuit of an “authentic” Latin American atmosphere. It feels as though it is eager to affirm its fidelity to the Colombian Caribbean setting, saturating the story with “traditional” elements that embody the region: frequent, unnecessary references to dancing and celebration, a soundtrack dominated by gaitas (a long flute crafted from cactus stem and charcoal) and drums, and an exaggerated accent specific to Colombia’s Caribbean coast, which sometimes comes across as forced. Many scenes could easily double as a tourism commercial showcasing the region’s exuberance.

While the series has avoided criticism for its representation and veracity, it has raised more substantive objections from Latin American intellectuals — namely, that adapting the novel is not only impossible but also suggestive of a worrying cultural trend: the tendency to simplify complex works of art in order to turn them into palatable entertainment. What’s at stake here is not the age-old question of whether books are better than movies. The crux of the matter lies in the challenge of translating a novel so varied in its literary techniques, with such a remarkable mastery of language and such a powerful vision of humanity, that it cannot be adapted for the screen without a significant loss of depth and density.

Books allow readers to imagine the story in their own way. No matter how precise or descriptive an author’s style may be, language inevitably leaves certain details of the world undefined — the thickness of a character’s eyebrows, for example. Readers fill in these gaps with their imagination. A film, however, presents a concrete world made of real objects, thereby fixing the story with specific features. This visual specificity prevents the reader from participating in the same creative operation fostered by literature. Now, one could say that this is a nonissue. Should we dismiss all audiovisual content on these grounds? Of course not.

But the case of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” is different because many consider that much of the novel’s artistry lies in its capacity to excite the reader’s imagination in ways few other books do. A novel set in modern-day London or New York may require less imaginative work from the reader, as it features familiar details that already exist in the collective imagination. With “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” however, Garcia Marquez set out to create an entirely new world that readers have no choice but to imagine, invoking settings, characters and situations without previous visual or cultural references. Although Garcia Marquez drew inspiration from the town of Aracataca, Colombia, to create Macondo, many of its details and settings are products of his own imagination. Besides, the novel’s narrative world is teeming with “magical” elements, such as a priest who levitates after drinking hot chocolate, a man perpetually followed by butterflies, and a light rain of yellow flowers. The novel cannot be reduced to this proliferation of fantastical elements, but its philosophical depth and tragic vision of history are thoroughly imbricated with this unruly display of inventiveness.

There is evidence that Garcia Marquez believed that fiction, perhaps more than any other art form, has the power to ignite the imagination in profoundly life-affirming ways. In a 1991 interview, he said that the reason why he didn’t want a film adaptation of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” was that a “novel, unlike the movies, leaves the reader a margin of creation that allows them to imagine the characters, the environments, and the situations as they think they are. … They reconstruct the novel in their imagination and create a novel for themselves. Now, you can’t do that in cinema.”

For almost 60 years, the novel only existed in the imaginations of millions. Now, readers can contrast their personal version of the novel with a visual counterpart. Will this diminish or enhance their experience of “One Hundred Years of Solitude”? For many, this is nothing but a troubling sign that we are increasingly eroding our capacity to imagine fictional worlds without visual references to guide us through. Nicolas Pernett, a writer and university professor, summarized this concern by saying that the Netflix adaptation constitutes nothing less than an assault on “purely literary imagination.”

Although I have thus far only seen the first four episodes, the series is not a one-to-one adaptation of the novel. It is not a didactic transposition that merely transforms words into visuals. Instead, it takes some creative liberties, and it is in these deviations that its most interesting elements are found.

The first notable change is the alteration of the chronological order. The novel begins with a forward displacement in time, with its iconic first line: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Part of what makes this sentence so striking is that its very first words prefigure an event that happens in the future. In contrast, the series starts at the novel’s conclusion, with an unknown individual reading a book that recounts the very story we are about to see. Therefore, the “main” story happens in the past. The result is a backward displacement in time.

This change works on two levels. First, it preserves the time-bending quality of the novel. But instead of replicating the book’s approach, it comes from the opposite direction. Second, this shift foregrounds something that the novel only reveals in its final pages: that the Buendia family story was written by someone who prophesied its events. In doing so, the series introduces from the outset the self-reflective nature of the narrative and sense of cyclical inevitability. The novel hints at these elements throughout, but it reserves them for a big reveal at its conclusion.

A second notable example is the addition of scenes that do not occur in the novel. In the second episode, for instance, there is a visually striking moment involving the brothers Jose Arcadio and Aureliano, in which they hunt and kill a pig together. This frenzied and violent display of childhood exhilaration culminates in a bonding moment, as the brothers press their blood-splattered faces together. Garcia Marquez never describes such a hunt, yet the scene proves effective because it foreshadows Aureliano’s violent future and lends weight to their father’s realization that his children are living in neglect and filth. Furthermore, it deepens an aspect the author did not explore in detail: the deep bond between the brothers. By adding this scene, their eventual separation becomes more symbolic and emotionally charged.

As this example shows, some of the series’s strongest moments arise when it takes itself and its characters seriously, recognizing that it, too, has something meaningful to say beyond what the novel suggests. Elsewhere the series strains to get every detail “right,” resembling a dutiful student reciting memorized lines. When it abandons this pretense, the series allows the characters and their conflicts to stand on their own, as part of the self-contained world of the narrative.

The series, paradoxically, succeeds by prioritizing interiority more than the novel does. With so much happening, the novel understandably does not delve deep into its characters’ emotions and inner struggles. For instance, the killing of Prudencio Aguilar, a man who insults Jose Arcadio Buendia (the patriarch of the Buendia family), is addressed briefly, dispatched in just a couple of pages. When Ursula, Jose Arcadio’s wife and the matriarch of the family, sees his ghost, her feelings are simply noted: “She was so moved.” The series, by contrast, lingers on the psychological burden that the killing imposes on Jose Arcadio and Ursula. In various scenes, the camera captures their troubled faces, the disruption of their daily routines, their guilt-ridden gestures during the trial for the murder of Prudencio Aguilar. This depth was not possible in the novel, as it moves forward at a dizzying pace, introducing characters and events in rapid succession. But the series stays with the main characters, offering a richer and more evocative portrayal of their inner lives. Moments like this make the Netflix adaptation an achievement that expands, rather than diminishes, the legacy of “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

In the decade since Garcia Marquez’s death, his legacy has been embroiled in controversy. The first storm hit in 2014, when the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin announced it had acquired the literary titan’s archive, consisting of original manuscripts, over 2,000 letters, photo albums, Smith Corona typewriters, computers and notebooks. Criticism and indignation soon followed, particularly from Colombia. How could the archive of the country’s most revered author have ended up, of all places, in the United States? The move was seen as a cultural and historical loss for the country. Even Colombia’s minister of culture at the time expressed dismay that the National Library was not chosen by the family as the archive’s repository. It was also well known that Garcia Marquez was critical of U.S. imperialism and maintained close ties with the Cuban communist regime. For almost three decades, he was barred from entering the U.S. because of his ties to the Fidel Castro regime and purportedly radical views. Now, his literary remains would lie in Texas.

The controversy grew so intense that the author’s children publicly stated on a popular radio station that the Colombian government had shown no interest in bidding for the archive. No less important was the practical matter of preserving delicate materials, such as paper and photographs, which are prone to degradation and institutional neglect. How would these objects be conserved to ensure they remained in good condition? Would they be made easily accessible to scholars and readers eager to examine their contents?

It is easy to see why the family decided that the Harry Ransom Center was one of the best institutions to address these practical concerns. The center is already home to the archives of figures like James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Doris Lessing and William Faulkner. It also holds some of Albert Einstein’s notes on relativity theory, one of the few remaining Gutenberg Bibles and the Niepce Heliograph, the earliest surviving photograph made in the camera obscura. Today, Garcia Marquez’s archive has been digitized and is available to the public through the center’s website.

The second storm hit early in 2024. “Until August,” Garcia Marquez’s unfinished last novel, was published simultaneously across the globe. He worked on it during the final years of his life, a period when his mental faculties began to decline. His memory was fading away with the onset of dementia. Although he published some of the novel’s chapters, he was never satisfied with the whole story and ultimately decided that the manuscript did not live up to his standards. In the prologue to the novel, Garcia Marquez’s sons state that he declared: “This book doesn’t work. It must be destroyed.” Nevertheless, both his family and publisher decided — once again — to go against his wishes. His editor unified the different versions, eliminated errors and repetitions, ordered the chapters and published the book.

“Until August” was met with mixed reviews and, once again, generated outcry. Many commentators found it corny, lackluster and vapid. The most common remark was that the novel was, at best, a mere shadow of Garcia Marquez’s most memorable novels. As The New York Times’ reviewer put it: “Reading ‘Until August’ is a bit like watching a great dancer, well past his prime, marking his ineradicable elegance in a few moves he can neither develop nor sustain.” While some of these criticisms are not unjustified, isn’t this way of reading the novel — comparing it to Garcia Marquez’s previous works, lamenting the decline of his creative energies — also a betrayal of the author? For, essentially, this approach holds the novel to the impossible standard set by earlier masterpieces, denying it the opportunity to stand on its own terms, as the author himself would have likely intended.

But what if “Until August” had turned out to be a late-style masterpiece, Garcia Marquez’s mind too muddled to recognize its true value, as his heirs claimed? Surely, few would have expressed disappointment in his executors. Their “betrayal” might even have been widely celebrated. To understand why, just take a look at the story of the work of Franz Kafka, one of the greatest authors of the 20th century.

According to a widely shared account, Kafka instructed Max Brod, his closest friend and literary executor, to burn his manuscripts and personal writings. Brod, acting in the name of literature, dismissed the request. Curiously, this (alleged) act of betrayal is rarely condemned in public discourse. No one laments that Brod spared from the fire such deeply personal texts as Kafka’s letter to his father. Perhaps what bothers readers is not that their favorite authors are betrayed but rather the impact that the betrayal has on their reading experiences. In Kafka’s case, Brod’s betrayal is condoned because it preserved an invaluable source of literary amazement; in Garcia Marquez’s case, his children’s betrayal risks affecting his image as a great writer. Applying different standards to judge one case over the other risks overlooking the fact that, in both cases, the same principle was violated: the express will of the dead.

At its core, a similar dynamic is unfolding with Netflix’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude”: The betrayal of Garcia Marquez’s wishes has become an excuse for commentators to voice their preexisting beliefs about literature, Netflix and the relationship between the two. Those who are skeptical about streaming entertainment or adaptations of major literary works are more prone to condemn the betrayal, while those who believe that anything can be adapted by the film industry tend to downplay it.

So, should we betray the will of our dead relatives? Were Garcia Marquez’s children right or wrong in selling the rights to Netflix and publishing “Until August”? I believe that focusing on these questions is ineffectual, not because they are unimportant, but because they are fundamentally unanswerable from an outsider’s perspective. There is no straightforward answer. Maybe they had valid reasons; maybe not. A truly satisfactory answer would require an understanding of the whole heap of nuances, tribulations and uncertainties surrounding the matter. We all face complex choices like this on a daily basis. Unlike the author’s children, however, we are spared the burden of having our decisions scrutinized by millions who know barely a tenth of the whole story. Shouldn’t this make us more hesitant about condemning or praising them?

If anything, “One Hundred Years of Solitude” teaches us that our treatment of family can be very difficult, if not impossible, to understand for outsiders, as it is shaped by trauma, unconscious or unspeakable desires, fear, resentment, devotion, unrequited love, misunderstanding and the ghosts of generations past. Most of the time, the novel tells us, our treatment of family may appear crazy, only truly making sense to ourselves.

I also think that this issue provides a great opportunity to move beyond fidelity as the benchmark for evaluating adaptations of literary works. Let’s agree that no adaptation will fully “do justice” to “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” So what? To have such an expectation reflects an ardent attachment to past experiences, to that thrust of exhilaration that swept us upon our very first reading of the novel. Once again, the novel cautions us precisely against clinging to experiences and passions gone by. Moreover, it warns us that perhaps there is nothing more dangerous and paralyzing than looking for happiness in the repetition of old cycles. As one character advises the few remaining young men in Macondo toward the end of the novel: “Always remember that the past was a lie, that memory has no return, that every spring gone by could never be recovered, and that the wildest and most tenacious love was, in the end, an ephemeral truth.” -newlinesmag.com / photo: imdb

VIDEO