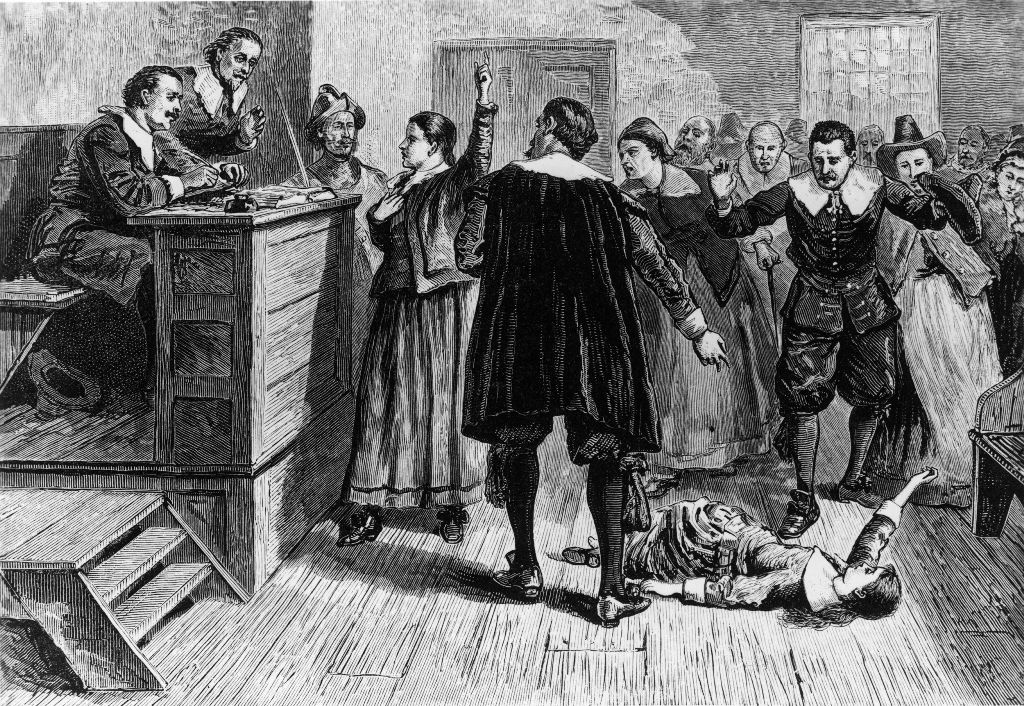

The last woman believed to have been executed in England for witchcraft may have avoided the gallows, according to new research.

Prof Mark Stoyle, a historian at the University of Southampton, believes a spelling error by a court official meant the accused woman was not hanged, but instead lived for several years.

Alice Molland was sentenced at Exeter Castle, Devon, in 1685 for “bewitching” three of her neighbours.

She was presumed to have been executed in the city’s Heavitree area in the same year, making her England’s last executed witch.

Prof Stoyle’s research suggests that the court documents from the time contained a spelling mistake, and Alice Molland might actually have been called Avis Molland.

He said: “Court records from the 17th century were written in Latin, and in this form it would only have taken a single mis-stroke of the clerk of the court’s pen to transform ‘Avicia’ (Avis) into ‘Alicia’ (Alice).

“Almost nothing is known about Alice’s life and attempts to illuminate it have failed.”

Molland was an unusual name in Exeter, so when Prof Stoyle saw a reference to an Avis Molland in some local archives, he was struck by its close resemblance.

He said: “I immediately asked myself, did Alice Molland ever exist? Is Alice, in fact, Avis?”

According to records from the time, Avis Molland had been married with three children – but they all died.

“By the time of the 1685 trial, Avis Molland was a poor, middle-aged widow, who was burdened with loss – precisely the kind of woman who was likely to be accused of witchcraft in early modern England,” Prof Stoyle said.

He added circumstantial evidence suggested Avis had been imprisoned at Exeter Castle at the same time as the trial for Alice was listed.

Avis died eight years after the supposed execution of Alice in 1693.

Had there been a simple spelling mistake, the last executed witches in England would in fact be the Bideford Three – Temperance Lloyd, Susannah Edwards and Mary Trembles – in 1682.

“The truth is, despite all my diligent searching, we may never know for sure whether history has got it wrong,” Prof Stoyle added. –Ethan Gudge, BBC News, CNN